Wang Qiushe is quite a memorable character in Gu Hua’s novel Small Town Called Hibiscus, a die-hard Maoist and a lazy bum for whom revolution is a chance to dispossess others and enrich himself. He seems a variation of Lu Xun’s Ah Q hoping to join the 1911 Republican Revolution so that he can have women and redistribute other people wealth. Perhaps this theatrical and archetypal recurrence deserves more attention from us than a nodding acknowledgment. There seems to be some deep tie between democratic revolution or political change on the one hand, and what Rene Girard (1923 – 2015) refers to as “mimetic rivalry“, where people who have less are only too happy to do what is necessary to deprive the rich of their rights.

During the Warring States, Lord Shang Yang, (390-338 BC), the reformer in the State of Chu, thought of this human propensity in relation to political order in his chapter Eliminating the Strong. “A country will disintegrate through chaos when the kind-hearted people rule over the treacherous; it will be well regulated and strong when the treacherous (奸民) control the kind-hearted people.” (国以善民治奸民者,必乱,至削。国以奸民治善民者,必制,至强.《去强》) His political philosophy as a legalist laid the foundation for the future unification of China, not Confucianism in favor of rule by virtue. Shang Yang’s attention to political deceit and deviousness as a means to an end is precursory to Niccolos Machiavelli (1469-1527) whose realism or Machiavellianism, though controversial, allowed us to understand the political history and realities both before and after the renaissance in the West.

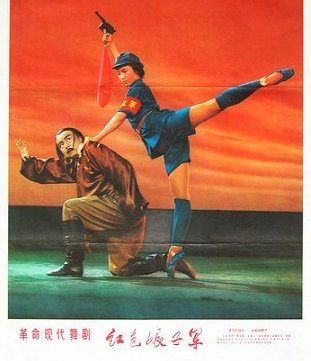

The same political wisdom is not lost to Mao Zedong (1889 – 1976), the leader of the Chinese Communist Party and revolutionary strategist. In his Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan, Mao argues that the “vanguards of the revolution” are the riffraff (痞子). Maoism is a marriage between idealism and realism, guiding the revolutionaries to do what must be done to achieve equality, freedom and democracy. It seems that great political changes in China, whether China’s unification in the 3th Century BC or the founding of the People’s Republic in the 20th Century, couldn’t have happened without the participation of the “treacherous” 奸民 or the “riffraff” 痞子. This fact about how social changes came about adds another dimension to Hegel’s idea of a nation’s history as the manifestation of a people‘s self-awareness as being free. Maybe historical subjects such as Wang Qiushe and Ah Q ought to redefine freedom in revolution for Hegel.