Take up a pro or con position with regard to socialism as it has existed in modern Chinese history. Anchor and defend your positionality in the readings assigned for this class. Group work is encouraged.

~~~~~~~~~

It is not easy to develop a handle to modern Chinese culture (and history). This is because history is volatile and, with change, there comes a variety of interpretations of past events, personages, or social issues. For example, modern China is a story of social transformation from a monarchy to a people’s democracy; or, it is the history of Chinese loss of their unique cultural identity and even humanity in the course of communist revolution; or, it is about the rise and decline of a people’s democracy made legitimate through Western liberal hegemony and its white mythologies; or, it is a record of the disintegration of world’s last authoritarian regime and decline of the absolute state power; or, it is a chronicle of social experiments culminating in greater democracy, freedom and equality that redefine Chinese-ness, or any such ideas that can be key to Chinese history.

Whatever perspective you adopt for interpreting the history of modern China, begin writing as early as possibly when you become settled in on a specific approach or preoccupation. You must substantiate your claim by adequate analysis of works in this class that are windows into the spiritual life of a people. As John Ruskin (1819-1900) said, “Great nations write their autobiographies in three manuscripts, the book of their deeds, the book of their words and the book of their art. Not one of these books can be understood unless we read the two others, but of the three the only trustworthy one is the last”. Thus, the truth (national autobiography or auto-ethnography?) that you see emerging from the works assigned throughout this semester on modern Chinese history has to be rooted in these “three manuscripts”

Oral Presentation Schedule:

- November 30,Thursday, 9:30 — 10:50

- December 5, Tuesday, 12:00 — 2:30

Some prompts and examples:

- How do you define the word “modern” in the case of China? Is it meaningful or how meaningful to talk about China in such polarities as “modern” and “traditional”? Give examples in the arts in which changes are represented as “progress” for the better.

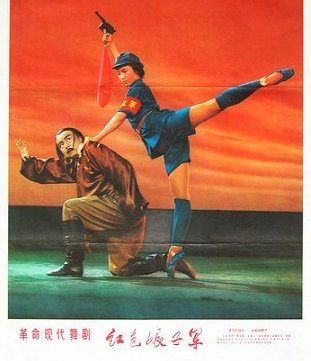

- “Class struggle”, a key component to Marxism and inseparable part of Chinese communism, gets elaborated in many works of fiction; what do these works tell you about social democracy to empower the poor or the proletariat? Give examples in the arts that inform you of the complexity in democratic revolutions.

- One of the ways to experience “culture” is through one’s collective identity such as gender, family, or nation/race; discuss the individual character(s) trying to fit himself or herself into one of these larger group identities. What cultural category seems most meaningful to the Chinese, individual, family or the nation?

- By nature, “revolution” is destructive or violent, and “culture” is orderly and rational. How do you understand this oxymoron “cultural revolution” since the May Fourth moving the Chinese nation from a monarch to a republic and to a people’s republic? Whom do the novelists and film directors show as fallen victims of destruction and violence? What has emerged as a new rational social order?

- What fictional scenarios are most often used to advance the cause of communism? What dramatic situations are frequently deployed to question Maoism? What emerges as the constant throughout the tumultuous “Century of the people”? How many different ways are there in which you find the Chinese imagine Justice and/or Freedom?